Tom’s Raritan River

Railroad Page

www.RaritanRiver-RR.com

Lucius Beebe Published “HighBall – A Pageant of Trains” in 1945.

The first chapter is

almost entirely dedicated to the Raritan River Railroad.

Questions? Comments?

Click

on the pictures or the links to see full size pictures from the book!

Pictures

are at the end of the article

www.raritanriver-rr.com/LBeebe/P00.JPG

HIGHBALL

A PAGEANT

OF TRAINS

by

LUCIUS BEEBE

1945

THE year 1888, in the world and the United States in

general, and in and around New York City in particular, was freighted with

nervous excitements. The eastern seaboard had at length dug itself out of the

drifts occasioned by the great blizzard which will forever be known by the year

of its occurrence, and Chester Conklin had succumbed to pneumonia occasioned

by falling in a snowdrift during the record fall. The i\’Ietropolitan

Opera Company of New York, in an era when boiled shirts and diamond tiaras were

the outward and visible symbols not alone of respectability but also of social

achievement, was vastly concerned over whether or not to include German opera

in its season’s repertoire. The German Kaiser was annoyed with France and was

shaking a noisy saber in its scabbard.

The columns of the New York Daily Tribune were

occupied by advertisements for Jaeckel the furrier’s

latest importation, a “seal Parisian walking jacket,” and a patent nostrum

against pneumonia called Denison’s Plaster whose typeset read ominously:

“Paraded Saturday, Died Monday!” The West still maintained a profound hold upon

the public imagination and Century Magazine’s frontier article for November was

entitled “Looking for Camp.” Classified advertisements of coachmen and grooms

seeking employment occupied half a column of agate type in the New York Herald.

In the world of railroading, too, brave doings were

toward. A newly financed and organized road, the Ridgefleld

and New York Railroad Company, was laying track from Danbury, Connecticut, to

New York City with an eye, doubtless, to making the celebrated Danbury Fair as

well as the hat building resources of that city more immediately accessible to

Manhattan. Throughout New York state the car stove had

been forbidden by law in all passenger equipment, and railroad executives were

shaking dubious heads over the expense of installing steam pipes in the wooden,

open-platform rolling stock of their properties. The Pennsylvania announced a

five per cent dividend on its common stock, a half of one per cent less than in 1887, but

the market bore up bravely under the intelligence. In Chicago, the Lake Shore

and Michigan Southern Company was having sharp words with the Chicago and

Western Indiana and filed a bill to restrain the latter road from interfering

with the business of laying Lake Shore iron across the tracks of the C. &

W. I. to join the main line of the Rock Island at Chic~go

Heights.

And across the New Jersey meadows, from New Brunswick

to South Amboy, Irish graders and track gangs were laying the fills and light

iron for what promised to be much more than a mere connecting railroad if ever

the tracks of what was then as now known as the Raritan River Railroad should

extend far enough across the main line of the Pennsylvania to join at Bound

Brook with the far-reaching systems of the Lehigh Valley, the Baltimore and

Ohio, the Central Railroad of New Jersey, and the Reading Company. Had this

ambitious plan been realized it is possible that the vast quantity of

industrial freight now syphoned out of South Amboy by

the Pennsylvania might have been diverted to other roads through the agency of

the Raritan River and the ambitious little project have ended as a through-haul

carrier in its own right. Legal and financial difficulties, however, limited

the Raritan River essentially to the trackage,

completed in 1890, between South Amboy and New Brunswick, with spurs to

Sayreville, Amclay, and the lead mines and docks that

lie adjacent to the Raritan River itself just around the bend to Perth Amboy

and the glistening reaches of Raritan Bay.

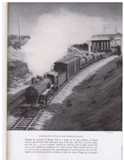

Time, however, has dealt more gently with the Raritan

than it has with many another short connecting line and today this little pike,

about twelve miles in length, operating without signals on telephonic dispatching

and with a motive power roster of only eight steam locomotives, is very much a

going concern and the last example of-big-time railroading and the grand manner

of the high iron in minuscule within easy distance of New York City. It is

standard-gage; its engines are more modern than many and many a valitudinarian kettle still in service along the mthn lines of the Wabash, C. & E. I., and Monon, and the sight of No. 5, a flange-stacked Baldwin

2-8-2 built in 1910, double-heading with No. i at the

head end of forty high cars and No. 7 pushing from behind as they breast the

grade of Bergen Hill is a picture to quicken the pulses and lift the

railroading heart. The morning mists of Raritan Bay are shivered with their

advance, the high stacks thunder with their exhaust, the coupled locomotives

roll and shudder perilously over the light iron, the heavy consist glides by,

the caboose and rear helper vanish again into the absorbent fog, and there has

come and gone a vision of railroading as true and authentic as any sight of the

Union Pacific’s ponderous Mallets fighting for life on Sherman Hill a few

miles~ west of Cheyenne.

The destinies of the Raritan are minor and homely

destinies involved with. brick kilns, coalyards and pie factories. A momentary touch of terror

and grandeur, perhaps, derives from the traffic stemming from the vast du Pont-Hercules explosive manufactury

at Parlin and another du

Pont subsidiary which manufactures cinema films hard by, and for these perilous

chores No. ii has had its stack fitted with an eye-filling spark arrester. But

mostly the road’s business is with lumberyards, pigmented clays, and the

delivery of tank cars to the Texas Company at Milltown. The Raritan’s last

passenger revenue, in the sum of $92, was earned in 1938. It once carried some

9,000 commuters weekly in its passenger and mixed~ trains, and handsome stone

and brick stations at Parlin and New Brunswick

testify to its prosperity as a passenger road only a few years ago. Today the

station at Parlin houses an orderly and well-staffed

freight bureau and business office. The sightly

little depot at the New Brunswick terminal has closed its waiting room and

boarded up its open fireplace, but its freight house is in good repair, and in

the station agent’s office a battery of telephones, filing cases, and

calendars, torn to the current month, from the Minneapolis & St. Louis

Railroad show it to be a going concern.

Very much as is the scheme of things on the West Shore

branch of the New York Central, where all westbound traffic is dispatched by

day and trains headed for New York run by night, the local freights of the

Raritan set out from South Amboy, where they have been made up during the night

in the classification yards of the New York and Long Branch and the Pennsylvania,

and roll westward during the morning hours. In the late afternoon the train

crews pick up eastbound cars from New Brunswick, Milltown, South River, Vandeventer; Gillespie, and Parlin,

from Sayreville Junction and Phoenix, and rest for the night in the home

roundhouse at South Amboy. No. 5 is the oldest engine in continuous service on

the Raritan and was the second No. 5 on its roster. The first No. 5, however,

is merely a legend, shrouded in mystery. All that anyone remembers is that it

was a 4-4-0 American type locomotive— quite the lady, but her origins and her

end are obscure. Just how a full-size steam locomotive could disappear or be

scrapped without a trace and leave behind it no record of its going on the

company books baffles H. Filskov, chief operations

officer, but that’s all anybody knows nowadays. Its most modern motive power is

No. 7, an o-6-o switcher built by Baldwin in 1919 and purchased by the Raritan

from the Chattahoochee Valley a few years later. Altogether the Raritan has stabled

twenty-one steamers in its roundhouse since 1890 and nowadays it makes a

practice of keeping seven engines in daily operation and one in the back shops

at all times.

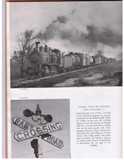

The right-of-way of the little road, for the most

part, is over New Jersey meadows and fresh ponds and inlets from the tidal

reaches of the Raritan River. There is a stiff grade through a lonely woodland

cut, in fall thickly populated by hunters, just east of Milltown. Deserted

spurs and moldering factory premises testify that once this stretch was alive

with small industrial projects, gravel pits, manufactories, and agricultural

undertakings. At South River the single iron passes over desolate marshes and

spans a curving arm of water within sight of the domed spires of the town’s

Orthodox Russian Church. At Parlin there are comparatively

spacious switching yards, a water tower of ancient brick and wooden design, and

a protected grade crossing, while a few miles farther on, the line crosses the

tremendous sand pits and narrow-gage railroad system of a

cement and gravel works. At no time, save perhaps in the deep woods of

Milltown, are the train crews of the Raritan out of sight of the tall

smokestacks and factory sites of industry, but even so, the illusion persists

that it is primarily a country railroad, a rural enterprise serving the

necessities of suburban existence.

The Raritan is, of course, the result of many and

varied antecedent circumstances in the history of New Jersey railroading. The

region it serves is an old one, industrially speaking, and a century and more

ago the cargo boats and passenger packets from Philadelphia went up the Delaware

River to Trenton and so inland by way of the Delaware and Raritan Canal to

reach tidewater again at New Brunswick. This pattern was broken by the

construction of the storied Camden and Amboy Railroad, now a part of the

Pennsylvania system. A clue to the ownership and management of the Raritan

River Railroad may be found in the person of its chief officer and

vice-president who is George LeBoutillier, executive

of the Pennsylvania Railroad, but the Raritan is still proud in its own motive

power, its own herald on its shiny red, double-truck cabooses, and the legend

of its own separate and individual entity lettered in gold on the tenders of its

locomotives which buck and heave valiantly ahead of thirty- and forty-car

trains over its twelve miles of main-line iron. Any inquiry into the internal

economy of the Raritan River will disclose that it is financially profitable,

both as an individual enterprise and as an agency for the collection and

distribution of revenue freight for the Pennsylvania, whose South Amboy

extension meets the mighty mainline at that crossroads of the railroad world,

Monmouth Junction. But more than this it is a homely and familiar factor in the

daily lives of the communities it serves and one which no other agency of

transport is likely to supplant in the immediate future. Buses and private

motor cars have absorbed its passenger traffic, but it is improbable that

trucks can, with economy and profit, handle its not inconsiderable bulk of

lumber, sand, coal, and other non-perishable merchandise.

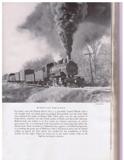

The Raritan River is the archetypal connecting

railroad, the dream railroad out of only yesterday. Its disintegrating ties,

sometimes laid in eccentric patterns, its archaically light rails and original

fluted fishplates laid down more than half a century ago, its hand operated

switches and homely informality of dispatching are redolent of wistful

railroading years, and it would surprise almost nobody if some morning No. 11

should come muttering down the grade from Phoenix with a bearded engineer in a

curly derby hat leaning out of the driver’s side. Its rolling stock (except its

brightly lacquered cabooses) bears the car heralds of other railroads; the

platforms of its passenger stations are peopled with commuting ghosts;

enthusiastic huntsmen have riddled the warning signs at its grade crossings.

But there is fire, metaphorically and factually, in its boilers; the main and

connecting rods clatter and are instinct with life; on the high (and only) iron

of the Raritan River there is traffic still. The Raritan River with its almost

irreducibly short mileage and well shopped stable of little locomotives is, to

be sure, only one of a multitude of short-haul railroads, each an individual

entity, a personality to the sentimental, a microcosm of the vast industry of

railroading to the more precise-minded.

by

LUCIUS BEEBE

1945

Pictures:

www.raritanriver-rr.com/LBeebe/P01.JPG

http://www.raritanriver-rr.com/LBeebe/P02.JPG

http://www.raritanriver-rr.com/LBeebe/P03.JPG

http://www.raritanriver-rr.com/LBeebe/P04.JPG

http://www.raritanriver-rr.com/LBeebe/P05.JPG

http://www.raritanriver-rr.com/LBeebe/P06.JPG

http://www.raritanriver-rr.com/LBeebe/P07.JPG

Questions? Comments?

Other

Fine Sites Dedicated to the Raritan River Railroad

http://www.geocities.com/transit383/rrhist.html

http://jcrhs.org/raritanriver.html

Here is an entire forum dedicated to

discussions of the RRRR!

www.railroad-line.com/forum/forum.asp?forum_id=2